What is emissions “rebaselining”? When should it be done?

- Author

- Henk HarmsenSenior carbon advisor

- Category

- Climate Essentials

- Topics

- Carbon

- Published

- 17 October 2023

Contents

- Where and when was the concept of rebaselining introduced?

- What is rebaselining in the context of carbon accounting?

- What is the difference between rebaselining and restatements?

- When should you consider rebaselining?

- How does rebaselining relate to other components of the GHG emission inventory?

- How do you get started with rebaselining?

- Recommendations

- Want to learn more about rebaselining with Sweep?

We explore "rebaselining" in the context of carbon emissions measurement, including when and how it should be performed and its potential impact on emissions reduction targets.

Organizations measure their greenhouse gas emission (GHG) reductions relative to their base year GHG – the baseline.

Circumstances may occur in which the GHG emissions in the reporting year can no longer be directly compared with this baseline. These circumstances include the discovery of (cumulative) errors, changes in GHG calculation methodologies, or changes in organizational scope, such as mergers and acquisitions.

In order to make comparison possible again, organizations must consider adjusting their baseline ("rebaselining"). In this blog post, we'll take a deep dive into what rebaselining means in the context of carbon accounting, when it should be done and how to get started.

Where and when was the concept of rebaselining introduced?

“Rebaselining” was first introduced in the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (WBCSD/WRI, 2004). Additional information was given in "Base year recalculation methodologies for structural changes” Appendix E to the GHG Protocol Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard Revised Edition", 2005.

We'll delve into this guidance, and compare it with requirements from GHG standards which were approved this year, namely CSRD E1 and IFRS S2.

What is rebaselining in the context of carbon accounting?

The GHG Protocol guidance specifies that the purpose of baseline recalculation is to ensure "meaningful and accuratecomparison of emissions data over time", whereas the ISO standard explains that the aim is to ensure the representativeness of the base-year emissions inventory". From this, it's apparent that rebaselining is done to allow "like with like" comparisons between the base-year GHG emissions and reported emissions of later years.

Baseline review and recalculation, when completed, serves two purposes: both emission trends and emission reductions can be calculated.

What is the difference between rebaselining and restatements?

Rebaselining is a recalculation of the baseline emissions. A restatement can cover any year but typically not the base-year. Restatement of emissions between the base-year and the previous reporting period is not mandatory. The term “restatement” is not formally defined in any of the GHG standards, and therefore, there are no specific requirements.

When should you consider rebaselining?

The GHG Protocol and the standards that are derived from it, approach base-year recalculation from three perspectives.

First, the circumstances which could trigger a base-year recalculation are set out. These include: discovery of (cumulative) errors, changes in GHG emission calculation methodology, and/or changes in the organization (e.g. mergers and acquisitions).

Second, some conditions are introduced which never trigger recalculation. Recalculation cannot be triggered by organic growth or decline of the reporting organization, or a change in its portfolio. Recalculation is also not required when emissions covered by the conditions listed in point 1 above are already covered in another scope of the emission inventory.

Third, the reporting organization must establish a base-year review and recalculation policy. This policy describes what triggers a recalculation, and how such a recalculation is done and documented. In other words, the reporting organization has considerable leeway in its approach to base-year recalculation, as long as it sticks with the conditions set out in points 1 and 2 above.

How does rebaselining relate to other components of the GHG emission inventory?

Every year, environmental managers completing their GHG inventory ask themselves three questions:

Is the base-year review and recalculation policy triggered?

What are the GHG emission reductions?

What are the GHG emission trends?

These questions have to be addressed in the same order. For example, assume that your GHG emissions are lower compared to the previous year only because of a scope change; in other words, neither GHG emission reductions nor GHG emissions trend occurred. Recalculating the base-year would then remove the difference in the year-to-year difference. Only after this base-year “reset” can emission reductions be assessed. After removing the GHG emission reductions the (residual) emissions trend can be seen. In summary, a base-year review, and if necessary a base-year recalculation is always done first.

From the above it also appears that there is a quantitative relationship between base-year recalculation, GHG emission reductions and GHG emission trends. If the recalculation target is set at 10%, then any emission reductions or trends below this percentage threshold become uncertain. In other words, it would not be clear to assess whether lower GHG emissions are the result of a small scope change or the result of an emission reduction initiative.

As outlined above, the GHG Protocol sets out the conditions under which a base-year recalculation should be considered, and the conditions under which it should never be considered. The possible scenarios are outlined below.

The scenario | Is a base-year recalculation needed? |

We produced less | No |

We shut down a facility | No |

We sold a facility | Yes |

Our production process became more efficient | No |

The external emission factor decreased | No |

The internal emission factor decreased | No |

A Global Warming Potential (GWP) decreased | No |

We started to outsource production | No |

We started to buy green electricity | No |

We made an error | Yes |

We made a series of small errors | Yes |

Now that you understand when to consider rebaselining, let's explore how to go about it.

How do you get started with rebaselining?

Below, we outline the step-by-step process that you should follow when rebaselining.

You must establish a base-year review and recalculation policy. This policy says when you recalculate the base-year, how you do it, and how the recalculation is documented.

You must state the base-year and the GHG emissions in that year.

If a base-year recalculation took place, then you must state this in your GHG report. You have to make clear what triggered the recalculation, what the changes are, and whether there are any remaining issues regarding comparing year-on-year GHG emissions.

The base-year must have a verifiable GHG inventory. The GHG Protocol and the associated ISO standard do not explicitly mention that these emissions must be representative. However, it is understood that a non-representative year does not help an organization to assess its emission reduction. The SBTi therefore states that the base-year must be recent and representative. For example a base-year covering the Covid-19 pandemic is not considered to be a valid baseline.

Recommendations

Base-year recalculation across the reporting period

The GHG Protocol recommends recalculating base years for the entire reporting period, even if changes occurred partway through the year (e.g., an acquisition in June). This avoids double recalculation (from June to December in the acquisition year and then in the subsequent reporting period) but is not addressed in ISO 14064-1:2018.

Integrating trigger monitoring into quality systems

To ensure accuracy, include regular checks and audits in your GHG quality system. These should encompass reviews of scope changes, calculation methods, and identified errors, among other relevant factors.

Aligning base-year triggers, uncertainty, and emission targets

Recognize the connection between base-year recalculation triggers, GHG inventory uncertainty, and your emission reduction targets and goals. A clear understanding of these links will enhance your sustainability strategy.

Correlation between baselines and GHG targets

New standards like CSRD EFRAG E1 and IFRS S2 emphasize that baselines and GHG targets are interconnected. It's beneficial to cross-reference discussions on targets and baselines to provide clarity.

Regular base-year reviews

According to EFRAG E1, companies must review their base year every five years starting from 2030, underscoring the evolving nature of company sustainability practices.

Intermediate year recalculation

While the GHG Protocol and ISO standard make recalculation of intermediate years optional, EFRAG E1 necessitates a base-year value change explanation, effectively making intermediate year recalculation a requirement.

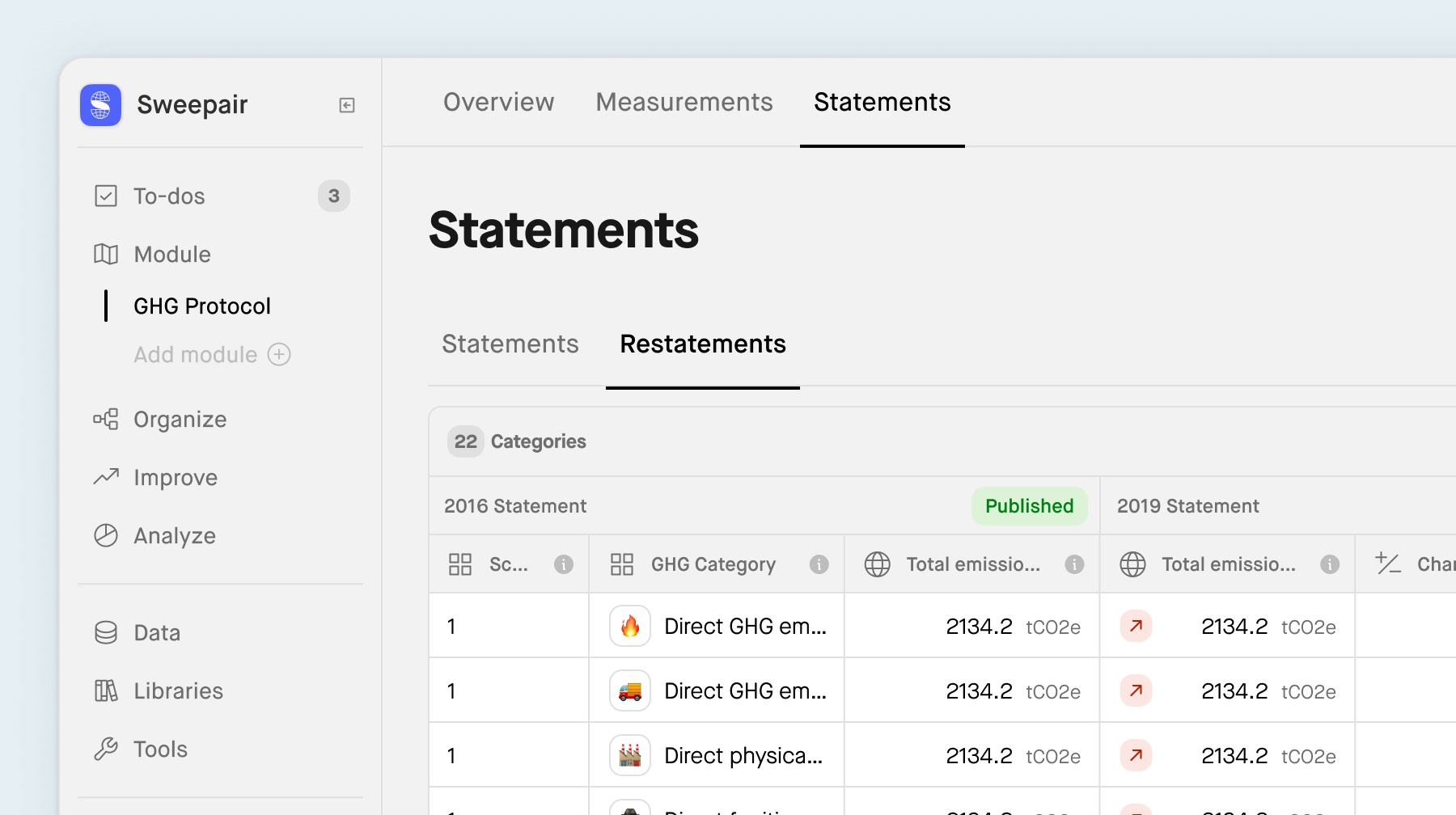

How rebaselining works in Sweep’s software:

- In the Sweep platform, you can generate annual carbon footprint statements and track their evolution over time.

- If there's a change in scope, you can conveniently update your baseline and choose the intermediary statements that require restatement.

- All modifications made between statements are meticulously documented to ensure a dependable, transparent, and auditable carbon footprint reporting process.

Want to learn more about rebaselining with Sweep?

Reach out today.

More stories

Track, report and act

Sweep helps you get your carbon on-track

Sign up to The Cleanup, our monthly climate newsletter

© Sweep 2024