The roadmap to 1.5°C of global warming

- Author

- Raphael GüllerCofounder and CPO

- Category

- Climate Essentials

- Topics

- Carbon

- Published

- 01 April 2021

Contents

- The most important crossroads in history

- Planning the route

- The Paris Agreement

- Why 2°C and why is 1.5°C preferable?

- What difference does 0.5°C make?

- What time should we arrive?

- The pathways to carbon reduction

- Energy – the big priority

- Transport – clean, green, fit and fast

- Food and agriculture – less meat, less waste, more greens

- Land use – planting for the future

- Industry – a second revolution

- Buildings – concrete plans

- Are we nearly there yet?

How do we stop climate breakdown? And keep our economies healthy at the same time? As most of the countries of the world grapple with their pledges on climate action, join us as we track the journey from good intentions to actual achievement.

The most important crossroads in history

Climate change is real, it’s happening now and it’s too late to reverse it. Even if we all stopped emitting any greenhouse gases this very second, the world will keep warming up for several decades. That’s because there’s a “lag” caused by all the CO2 that we’ve already emitted over the last couple of centuries and that’s stored in the ocean.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. We can stop climate catastrophe, and we can even create a rather wonderful future where the planet is a better place to live.

We know what we need to do. Almost all the countries in the world have agreed on that and have committed themselves to doing it (see Paris Agreement below). And, while some countries were off to a slow start, things are starting to look up.

Businesses, industries and governments are pouring money and brainpower into finding ways to cut their emissions. We have the means and we have the technology at hand, right now – all we need to do is to put it into action. Let’s go on a road trip (on a bicycle, naturally) to a brighter, low-carbon, future.

Planning the route

The Paris Agreement

On the night of 12 December 2015, history was made in Paris. Thousands of delegates at the United Nations’ 21st Conference of Parties (COP) ended two fraught weeks of negotiation and, to cheers and standing ovations, the gavel came down on the Paris Agreement.

The agreement set out legally binding targets for all countries, rich and poor, for slashing greenhouse gas emissions. As of January 2021, 197 countries – pretty much all the major carbon-emitting nations in the world – had signed up. Which is a good start (even though, as it stands, if each of those nations implement their pledge commitments, known as National Determined Contributions, we will see global warming of 3.5°C).

The goal: to limit global warming in this century to below 2°C – and preferably to 1.5°C degrees. To do this, countries must reduce their emissions by half by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050.

Why 2°C and why is 1.5°C preferable?

By the end of 2017, the planet was, on average, more than 1°C warmer than since records began in 1880 and we’re already seeing the effects this has had on the climate. Glaciers have shrunk. Heatwaves happen more often, wildfire seasons are longer. Some places have had unprecedented rainfall, while others are experiencing drought. Trees are flowering earlier – the famous cherry blossom season in Japan is now weeks earlier than 10 years ago. And some bird species that used to migrate to warmer climes in the winter don’t need to bother anymore.

At the Paris conference, the global community agreed that if we limit global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial times, these climate effects would still be manageable. If we do nothing, temperatures will continue to rise to 6°C, which doesn’t bear thinking about.

Since the Paris Agreement, however, scientists have come to believe that the 2°C scenario is too optimistic. What we really, really need to do is to limit the temperature rise to 1.5°C.

What difference does 0.5°C make?

Turns out, the difference is huge. According to a report released in 2018 by the UN’s IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), half a degree warmer means a world with significantly more poverty, extreme heat, sea level rises, habitat loss and drought.

🥵 Heatwaves

14% of the world’s population | 37% of the world’s population |

|---|---|

1.5°C | 2°C |

More people will be exposed to severe heatwaves at least once every five years. At 2°C, the deadly heatwaves that India and Pakistan saw in 2015 may occur every year.

🌵 Drought

+350m | +411m |

|---|---|

1.5°C | 2°C |

More people will be exposed to water scarcity in 2050 at both temperatures, but it will be much more widespread and affect millions more at 2°C.

🧊 Arctic sea ice

Every 100 years | Every 10 years |

|---|---|

1.5°C | 2°C |

The frequency that the Arctic will be ice-free over the summer. That’s bad news because Arctic ice helps to mitigate against climate change.

What time should we arrive?

So let’s focus on the target of 1.5°C because anything higher isn’t an option. And because, on a more positive note, it’s a target that can be reached. As long as we stick to the dates set out in the Paris Agreement: 50% reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2050.

While 2050 sounds unimaginably far in the future, 2030 is the real deadline. Because here’s the not so good news. The conditions that make our planet inhabitable are like traffic on a motorway. If one thing stops working, everything comes crashing into it in an almighty pile-up.

A little more CO2 in the atmosphere doesn’t always result in an equal amount of global warming. To give just two examples:

Temperatures rise. The ice caps melt. The sun’s rays are absorbed by the sea, rather than reflected by snow and ice. Methane, a greenhouse gas that was captured under the ice, will be released and add even more emissions to the atmosphere. Temperatures rise even more.

Temperatures rise. Forests get dryer. A simple spark can start massive wildfires. This releases all the CO2 that had been captured in the trees, and it means less CO2 is removed from the atmosphere in the future. Temperatures rise even more.

So, halving the emissions by 2030 is the bare minimum we need to achieve in order to avoid an irreversible vicious cycle.

What is net zero?

Net Zero is when the amount of greenhouse gas we emit is the same as the amount that is removed from the atmosphere. Imagine a bath with both taps running. The water coming from the taps represents the carbon we’re pumping out into the atmosphere. If you open the plughole and drain away the same amount of water (carbon removal), you get to the ‘net zero’ balance. Note that only CO2 can be removed. Other gases such as nitrous oxide can only be reduced.

The Earth already has built-in carbon removal solutions – healthy plants, oceans and soil all remove carbon from the atmosphere and store it (known as sequestration). There are also man-made carbon sinks known as negative emissions technologies (NETs) that sequester carbon by, for example, capturing it and injecting it into the ocean floor or underground rock. The jury is still out on the virtues of this technology, and reducing emissions in the first place should still be the priority.

The pathways to carbon reduction

All the countries in the Paris Agreement have pledged to cut their greenhouse gas emissions by the above dates. The next question is, how? And the answer is, it’s complicated.

On a country level, each one has different sources of emissions, whether it’s agriculture or industry, construction or transport. And some have the economy and infrastructure to cut their emissions – in other words, they can afford to while others can’t.

Industries, sectors and individual businesses have a big part to play as well, with many setting their own targets for reducing emissions. And it gets even more complicated when we start talking about carbon trading and offsetting.

So let’s keep things simple. Here are some of the main ways to get to a low-carbon future. There’s no single ‘silver bullet’ – we have to use a combination of all these approaches. But the great thing is that, by doing so, we might accidentally make life better for everyone at the same time as saving the planet.

Energy – the big priority

Energy, whether it’s from electricity, heat, transport or industrial processes, accounts for the majority – around 76% – of greenhouse gas emissions. If we invest in renewable energy instead of fossil fuels, not only do we cut emissions drastically, but the cheaper and more plentiful the energy supply becomes. If governments provide the financial mechanisms such as tax incentives, to support the renewables industry, they can provide more jobs and clean, affordable energy for everyone. And as a bonus, the air will be much cleaner and healthier too.

Transport – clean, green, fit and fast

Globally, transport contributes to around a quarter of CO2 emissions, and road vehicles – cars, trucks, buses and motorbikes – account for nearly three quarters of those. Switching to greener power such as biofuels, hydrogen or electricity from renewable sources is one way to address this. But so is investing in better public transport and making it easier for people to cycle or walk instead of taking the car. And that also results in fitter, healthier citizens with calf muscles to die for.

Food and agriculture – less meat, less waste, more greens

The world's food systems produces about a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions and twice as many come from land used for livestock as those used for crops for us to eat. So one way to reduce emissions is to encourage more people to ditch the burgers and switch to a plant-based diet. Food waste – both from the production and distribution process and by consumers – is another big source of emissions, so addressing that is a good idea, too.

Land use – planting for the future

The humble tree is a brilliant carbon-absorbing machine. Plants are perhaps our most powerful weapons when it comes to tackling climate change. It’s been estimated that nature-based solutions could be used to sequester around 9bn tonnes of CO2 every year by 2030. But we need to stop deforestation first. Planting forests while continuing to destroy them has zero effect. Reforestation, rewilding and greening our cities has all kinds of other benefits too, such as cleaner air, cooler and quieter streets and more habitat for wildlife – not to mention that sense of wellbeing that we get from being surrounded by nature.

Industry – a second revolution

Industry, the sector that makes all the products and raw materials and general stuff that we use every day, produces emissions in all kinds of ways, from burning fossil fuels to chemical reactions. Using cleaner fuel and recycled raw materials, as well as upgrading to more efficient technology, will help. And building the low carbon industries of the future, such as renewable energy and manufacturing electric vehicles, will help even more.

Buildings – concrete plans

Stay right where you are, building sector – you’ve got a lot to answer for, too. Another big emitter, the construction industry could reduce greenhouse gases by 50% through more efficient use of building space, energy efficient refurbishment and net zero-emission building methods. That means, for example, using circular construction (a zero-waste system where building materials and products are recycled and re-used) and heavy vehicles that run on biofuel instead of fossil fuel.

Are we nearly there yet?

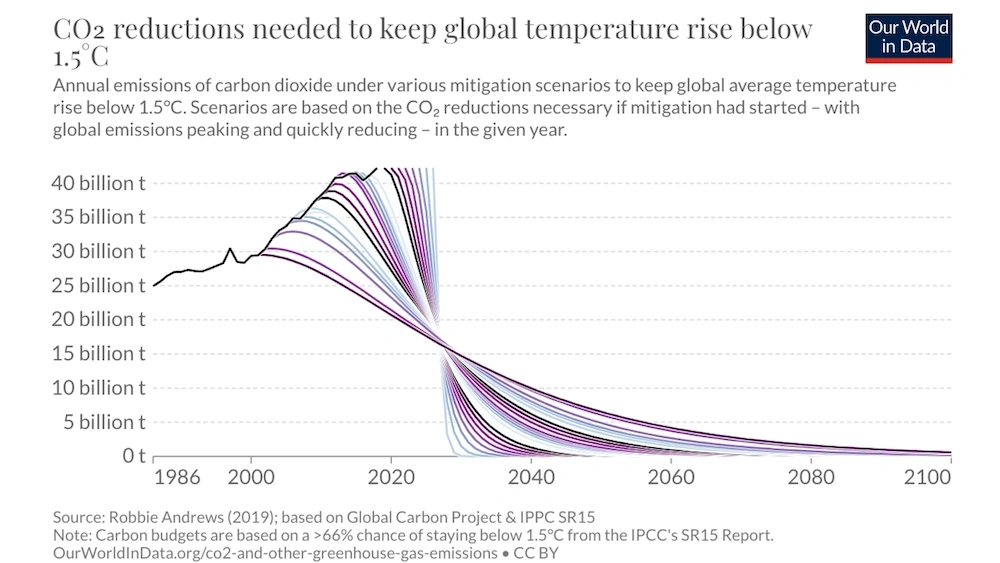

Progress has been made in almost all of the areas above. But we need to do much more. Many countries are falling short of the targets that were pledged and globally we are nowhere near reducing enough emissions to keep temperature rises to below 1.5C. The chart below shows the precipitous drop in emissions we need.

Global emissions over time, and by how much we need to cut them to hit 1.5°C.

But that doesn’t mean that we can’t do it. More and more countries, regions, cities and companies are setting net zero emissions targets and finding amazing ways to reach them, and as the momentum builds, the more likely we are to catch up. Here are just some of the signs that things are accelerating:

- Since 2015, more than 1,000 companies have set science-based emissions reduction targets. These include big brands, from Chanel to Nestlé.

- The Race to Zero campaign, backed by the UNFCCC, involves over 3,500 members, including 23 regions, 708 cities, 2,162 companies, 571 higher education institutions, and 127 investors, alone making up over 15% of the global economy.

- More than 130 private banks – one-third of the global banking sector – have signed up to the Principles for Responsible Banking, a framework that aligns banking practices with the Paris Agreement.

- There’s growing political support for more ambitious targets. Countries such as the UK, France, Norway and Sweden are adopting laws to reach net zero emissions by 2050 or earlier.

And there are better, and more competitive climate solutions being developed all the time, from ingenious ways to sequester carbon to reforestation schemes and sustainable farming (for more on those, read our Guide to Climate Solutions).

So we can still make it in time. We just need to really get everyone on board and put our foot on the gas (or bicycle pedal, remember). That means everyone taking action, from national governments to city planners, from tiny start-ups to multinational conglomerates, and every individual, starting from now.

Further reading

Photos by Augustine Wong

More stories

Track, report and act

Sweep helps you get your carbon on-track

Sign up to The Cleanup, our monthly climate newsletter

© Sweep 2024