The 101 of climate change

- Author

- Louise BanburyWriter

- Category

- Climate Essentials

- Topics

- Carbon

- Published

- 27 April 2021

Contents

- 1. What is climate change? Is it the same as global warming?

- 2. But hasn’t the earth always been warming and cooling?

- 3. What’s the evidence of climate change?

- 4. Okay, so humans are changing the climate. But how?

- 5. What are the greenhouse gases?

- 6. What is the greenhouse effect?

- 7. What are carbon sinks?

- 8. What will happen if temperatures keep rising?

- 9. So it’s too late and we’re all doomed…..

- 10. Phew. So how do we reach net zero emissions?

What is climate change, what causes it and what can we do about it? We go back to basics with a super-simple, everything-you-ever-wanted-to-ask primer on climate change.

1. What is climate change? Is it the same as global warming?

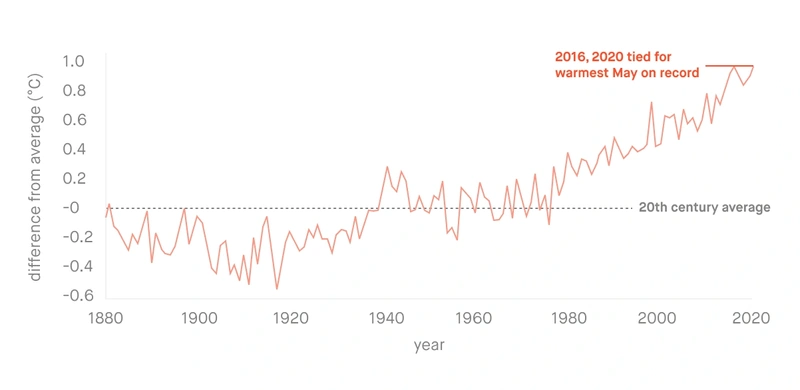

When we talk about climate change, we mean long-term, large-scale shifts in global weather patterns. Global warming – the heating up of the earth’s surface – is what causes these shifts. The earth has been warming rapidly for over a century and today the average temperature is around 15°C. That’s 1.18°C higher than it was before the Industrial Revolution of the mid 1800s, as you can see in the chart below.

Global average temperature in May, 1895–2020. Source: NOAA Climate.gov

This 1.18°C rise in temperature doesn’t sound like much, but it is a big deal as far as the climate is concerned. It causes everything from melting ice caps and rising sea levels to more frequent extreme weather events such as heatwaves and heavy snow or rainfall, flooding, drought and wildfires.

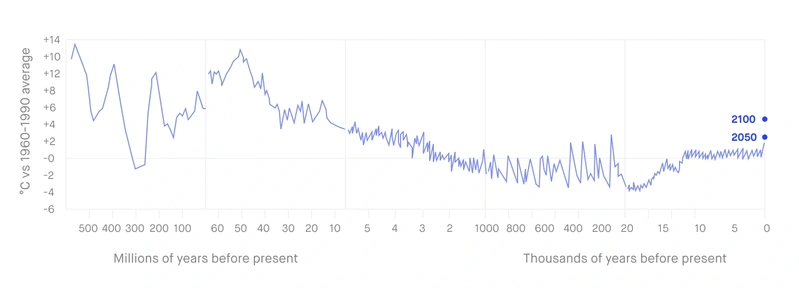

2. But hasn’t the earth always been warming and cooling?

Yes, climate change has been a thing, ever since Planet Earth was a thing. But change has, in the past, happened very, very slowly. We’re talking over hundreds of thousands of years.

The way the earth orbits around and tilts towards the sun happens in predictable cycles. These cycles determine how much of the sun’s energy reaches the earth – and they’re what cause ice ages or periods where the ice melts.

Over the past 800,000 years or so, these ice/melt cycles have happened every 100,000 years. The chart below shows the earth’s temperature fluctuations over millennia.

Estimates of the earth’s average temperature, from 540 million years ago to 2015. Source: Glen Fergus

These natural cycles don’t explain the rapid rise in temperatures that have happened in the past 150 years. Current warming is about 10 times faster than the average rate of warming that usually happens after an ice age.

Most of the warming in the last century has occurred in the past 40 years, with the seven most recent years being the warmest. And 19 of the warmest years have happened since 2000.

3. What’s the evidence of climate change?

Scientists have been gathering all kinds of data about our planet and its climate over many decades, using earth-orbiting satellites and other technological wizardry. And ancient evidence, drawn from ice cores, tree rings and sedimentary rocks, can tell them about the planet’s climate long before temperature records began.

Scientists have found a number of signals signals that the climate is changing rapidly and dramatically, including:

Warming ocean: The ocean absorbs 90% of the excess heat caused by global warming, and since 1969, the top 100 metres of ocean have warmed more than 0.33°C.

Rising sea levels: The global sea level rose about 20cm in the last century. but in the past 20 years, it rose nearly twice as fast as it did in the past 100 years. It’s rising because the ice sheets and glaciers are melting and because seawater expands as it warms.

Extreme weather events: There has been a ‘staggering rise’ in extreme weather events in the past 20 years. Major floods have more than doubled, the number of severe storms has risen 40%, and there have been major increases in droughts, wildfires, and heatwaves.

Shrinking ice sheets. The ice in the Arctic is already 65% thinner than it was in 1975, and we could see ice-free summers in the Arctic by the middle of this century.

🌸 Sakura: a sign of the times

In Japan, the cherry tree is loved for its blossom (Sakura) which is seen as symbolic of life, death and rebirth and is revered in poetry, art and literature. It’s also very sensitive to temperature changes, which is why it’s a useful source of data on climate change.

Ever since 1953, the Japan Meteorological Agency has tracked 58 cherry trees and has found that they are blossoming earlier and earlier. The blossoms used to reach their peak in April, just as the new school year was beginning. Now, they're past their best by the end of March.

In Kyoto, the 2020 blossom peak was on 26 March, a full 10 days before the 30-year average. And it’s no surprise that the temperatures tell a similar story. The average temperature for March in Kyoto has climbed to 10.6°C in 2020 from 8.6°C in 1953.

4. Okay, so humans are changing the climate. But how?

In a nutshell, the Industrial Revolution.

In the mid-1800s, we started burning more fossil fuels (oil, coal and natural gas), to power the new mills, factories and locomotives. Ever since then we have been increasing the concentration of CO2 and other gases in the atmosphere (because the process of burning fossil fuels combines carbon with oxygen in the air).

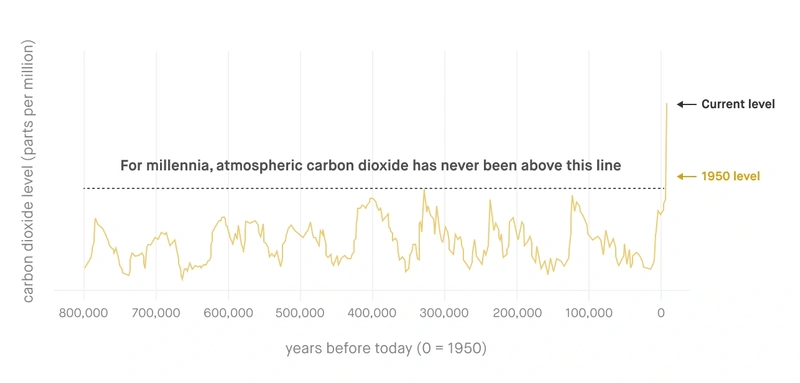

Human activities have raised the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere by 48% since 1850. This kind of increase has happened naturally before, but in the past it took over 20,000 years, as shown below.

This graph, based on the comparison of atmospheric samples contained in ice cores and more recent direct measurements, provides evidence that atmospheric CO2 has increased since the Industrial Revolution. Source: climate.nasa.gov

We weren’t to know, when we first started shovelling coal into furnaces, just how bad an idea it would be. But since the 1980s we have known that the gases we’ve been pumping into the atmosphere cause the greenhouse effect. And it’s not a pleasant kind of greenhouse to be in.

5. What are the greenhouse gases?

Greenhouse gases are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, nitrogen oxide, and fluorinated gases (CFCs). They also include water vapour and ozone.

Some greenhouse gases last longer than others, and some contribute more to the greenhouse effect than others. Just how much of a contribution depends on how much heat it absorbs, how much it re-radiates and how much of it is in the atmosphere.

In descending order, the gases that contribute most to the greenhouse effect are water vapour, CO2, nitrous oxide, methane and ozone. (Note that water vapour, although it traps heat and makes up 95% of the atmosphere, hangs around for a really short time, so it’s not considered a climate changer.)

Weighing up emissions: tC02e

The standard measuring unit for greenhouse gas emissions is tCO2e. It stands for tonnes (t) of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent (e), and can be used to measure any emission, regardless of whether it’s from carbon dioxide or another gas, such as methane.

It takes into account the fact that some gases contribute more to the greenhouse effect than others. Methane, for example, has 28 times the heat-trapping capacity of CO2 over a period of 100 years. So a tonne of methane is 28 tCO2e.

6. What is the greenhouse effect?

It’s what happens when too many of these greenhouse gases collect in the atmosphere.

The sun’s rays shine on the earth’s surface and get reflected back. The gases allow the sun’s rays through to the earth, but they trap the heat that gets reflected back. They behave like a blanket for our planet – without them, we’d freeze. But too much and we overheat. Big time. And, as we’ve seen, there’s far too much of them right now.

7. What are carbon sinks?

At the same time as pouring more greenhouse gases into the air than ever, we’ve been destroying the ecosystems that naturally filter them out. Burning down the rainforests, destroying wildlife, polluting the ocean – that sort of thing.

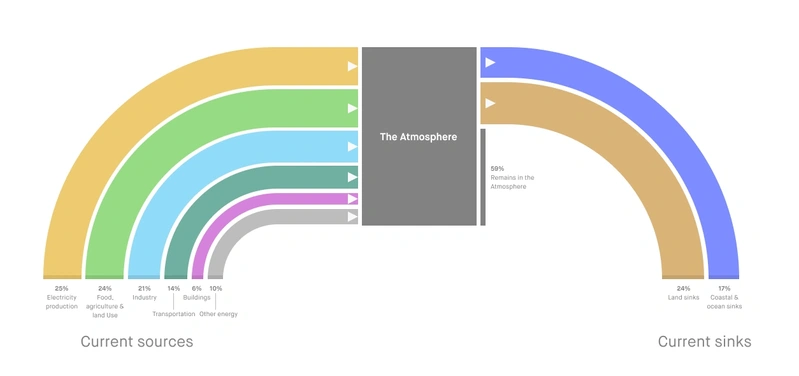

The trouble is these ecosystems – the forests, oceans, grasslands and soil etc. – act as natural ‘carbon sinks’ that absorb the gases and store them (a process known as sequestering). The diagram below shows the massive imbalance we have now between greenhouse gas emissions and the amount being absorbed by natural sinks.

Emissions sources and natural sinks. Source: Project Drawdown

And that’s not the only imbalance. The more we heat up the planet, the more we put its natural ability to keep itself cool out of whack.

Remember the melting ice sheets we mentioned earlier? Snow and ice helps cool the earth’s temperature by reflecting heat. Global warming means there’s less snow and ice, so less heat gets reflected and more gets absorbed by the ocean. Which means everything gets even hotter.

And when the ice melts, it releases methane, which adds to the greenhouse effect. So it gets hotter still. And so on, in a very vicious circle.

8. What will happen if temperatures keep rising?

We can’t predict the future. But scientists can have a very well-educated guess by running computer models based on various scenarios. They believe that if we don’t act drastically to cut our greenhouse gas emissions, temperatures could rise by between 3°C and 5°C by the end of the 21st century.

Even if we cut our emissions, the effects of climate change will continue because large bodies of water and ice can take hundreds of years to respond to changes in temperature. And it takes CO2 decades to be removed from the atmosphere.

So the droughts, fires, floods and extreme weather will keep on coming. And get much worse. There’ll be food shortages and there’ll be conflict over land and water resources. More plants and animal species will become extinct. The health of millions of people could be threatened by increases in malaria, water-borne disease and malnutrition.

And, although it’s the wealthier countries that produce most greenhouse gas emissions, it’s the poorer countries that will see most of the severe effects, because they have fewer resources to adapt.

9. So it’s too late and we’re all doomed…..

Not necessarily. If we act now, we can still stop climate catastrophe.

The UN is leading a worldwide effort to stabilise greenhouse-gas emissions. In 2015, 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement, with the goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C, and preferably 1.5°C. This will keep the effects of climate change manageable.

To reach this goal, we must reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050 (net zero is where there is a balance between gases being emitted and those being removed from the atmosphere). If this target is met, we can keep the temperature rise to 1.5°C and escape the worst effects.

10. Phew. So how do we reach net zero emissions?

That’s the spirit.

More and more countries, regions and cities are finding ways to cut their emissions, from investing in renewable energy to enabling people to walk and cycle instead of taking the car.

Companies, meanwhile, are setting their own net zero targets, and committing to climate programmes [link to how to run a climate programme] that help them identify, report and, most importantly, reduce their emissions.

We are still a long way off and much more needs to be done. But the will and the momentum is growing every day. And you can be part of it – start by reading our Roadmap to the future [link], and come on board the journey to 1.5°C.

More stories

Track, report and act

Sweep helps you get your carbon on-track

Sign up to The Cleanup, our monthly climate newsletter

© Sweep 2024